Late 1970s Kerkrade, a Dutch coal town across the German border from Aachen. High unemployment. Hemmed in by heavy-browed slag heaps. The futures on offer are coal, border-town crime, and escape. But every teenagers’ ‘now’ is being in a band. Metal heads or synth kids, mutually exclusive. Kids scrub off the town’s black coal dust for a night out and emerge from music clubs drenched in sweat and blackened again by smoke from Kiss cover bands’ pyrotechnics.

Sparks start fires. Fires that catch across a generation or fuel a lifelong passion. The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. David Bowie and Mick Ronson playing ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops. For Vincent Wehren the spark came through ‘Countdown’, the music show on Dutch TV channel Veronica. He was seven when Kiss played ‘I Was Made For Loving You’ and it set the schoolyard alight. The next day Vincent and friends scrambled to pick a member of Kiss to be and started arming themselves with homemade, slack-stringed, wooden guitars. Vincent claimed front man Paul Stanley and the fire started.

The first record that Vincent owned was ‘Kiss Alive II’ – the double, the pyrotechnics, the works. It cost his grandmother 38 Guilder at Downtown Records.

At 13, he joined local band Sweetz from a Stranger (hard to imagine that name not causing some discomfort today). The next band, Target, was Vincent’s band. Fifteen-year-old Vincent, brother-in-law Marc Delaet, drummer Eric Reulings, bass player Marc Bosten. Rock and roll histories would be nothing without discarded band names so Target gave way to Sequence, and Sequence put down $800 for studio time at Twin Music in Brunssum. The four-track demo was their calling card for bookers at local bars and clubs. Victory at a local Battle of the Bands paid out in more studio time. And then Golden Earring came to town.

Golden Earring became Netherlands rock royalty when they made number one in the US with Radar Love in 1973. A decade and more later, they were coming through town to play the local Rodahal Arena. Sequence, now with local legend Jos Wetzelaer on drums, secured an unlikely support slot, raced through an adrenaline-fueled set at a ridiculous lick in front of 3,000, and twenty minutes later emerged local heroes.

Vincent was set up to step up. He had caught the eye of Gino Taihuttu, bluesman and leader of Venlo-based Gin on the Rocks. Gino was looking for a front man. Vincent graduated from the boondocks to the bigger city, local to national Battle of the Bands champions. For all its challenges, Kerkrade had none of the exoticism or edge of Venlo. Gin on the Rocks HQ was behind the railway yard, in the heart of the Ambonese community. The constant stereo sound of shunting engines in one ear, passing traffic in the other.

Gin on the Rocks were top notch musicians, and they’d been around. Vincent was seventeen, the rest of the band ten years older. They were there to play. The cycle ran: write songs, practice, fall asleep to the bands’ picks on the stereo (Miles, Coltrane or Joe Zawinul for Arwen, rock and blues for Gino), wake up, write, practice, repeat. Arjen was keyboard player Arjen Meuleman. He had perfect pitch and a party trick. Play a chord, any impossible chord. Naming it wasn’t the trick. Arjen would walk over to the record collection and pull out a song that started with it.

Gin on the Rocks got picked up by German label Steamhammer and decamped to Horus Sound Studio in Hanover to re-record their debut album, ‘Coolest Groove’. Steamhammer put 150,000 Deutschmarks into the album. When Vincent later came to leave the band, he was on the hook for his twenty percent of those costs (royalties for his lyrics and time hadn’t made a dent). His then manager gave him a steer: “Go and make a nuisance of yourself”. He drove the four hours to Hannover, with a new driving license and Fiat Uno, and walked into label boss Manfred’s office. Vincent had a sleeping bag and he wasn’t afraid to use it. He’d be camping in the office until Steamhammer let him out of the contract. One heavy sigh and an “I don’t need this” look later, he was free and gone.

‘Coolest Groove’ sold pretty well locally. They picked up a following in the Netherlands and Germany, and a small fan base in Japan. They played thirty to forty gigs a year. Clubs, festivals, everything in between. Some stand out. Arnhem hockey stadium on Liberation Day the day after Vincent’s first daughter, Cheyenne, was born. 1990’s Bospop in Weert, which survives online.

With a young family, shuttling between Venlo and Kerkrade was hard. Vincent credits Gino with much of his musical education, for the transition from heavy metal kid to rock and blues man. Guitar-playing and songwriting chops boosted, he was ready to be more than the singer in someone else’s band.

Winston Berrisford Gawke was raised in India. His father, Cedric, was a tiger hunter in the days of the Raj. Winston was an out-and-out showbiz guy. Winston G and the Wicked featured Marc Bolan and Top Topham (the Yardbirds guitarist who made way for Eric Clapton). Winston hosted an early 70s TV show in the UK before making a music career in the Netherlands with his band Cobra. Surviving video pulls his act straight out of Woodstock central casting – bare chested, flowing locks, swagger and textbook mic-wielding.

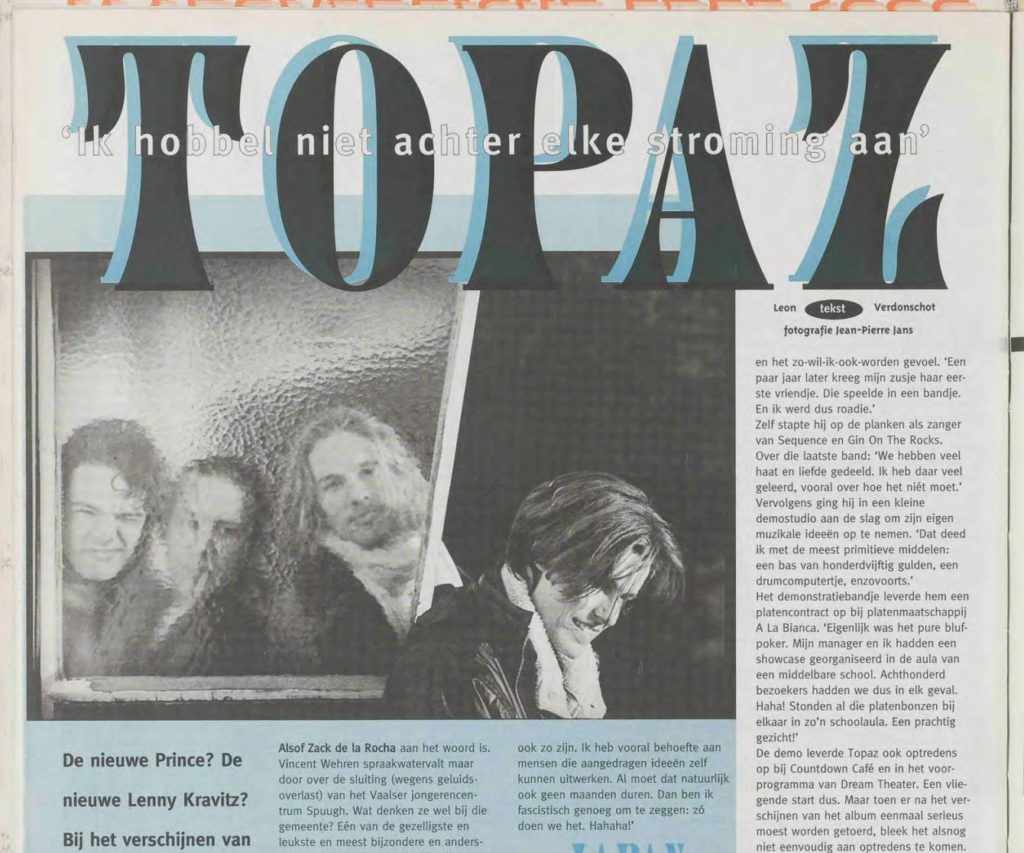

Vincent had made an early impression and, when he was ready to break out, Winston was there to help him pull together and manage his band. Topaz featured Oscar Kraal on drums (who would later play with Candy Dulfer), Nick Mulder on keyboards, Dave Bordeaux on bass and Marcel Singor on guitar (later a member of Dutch legends Kayak, he would go on to jam with Steve Vai and is next to be seen out on tour with Fish).

Topaz got signed to Dutch label Alabianca Records by Henri Lessing, a Tyrolean Italian A&R man who quickly put them in the studio. ‘The Door’ was recorded in Steelmill Studios using an analog CADAC A-Type recording desk. Rumor had it that it was the same one used on Bohemian Rhapsody. User-friendly it was not. Switching five channels at once meant five hands or one long strip of sticky tape across the five controls and a sharp, well-timed tug. The album was Vincent’s songs, production, vocals and musicianship (save drums and some bass), a precocious breadth of roles that led some eager concert promoters to pepper posters with Prince parallels.

Henry Lessing had beaten out Sony to sign Topaz after their first big show, for which Winston had pushed the boat out. There was a film truck, pyrotechnics, and a top-notch sound setup. They played in front of a sweaty, energetic young crowd at Zoetermeer College in 1992. The show survives on YouTube. The musicianship is tight, the showmanship self-assured. These guys know what they’re doing. There’s a cover of Purple Rain before everyone played a cover of Purple Rain.

The band was in demand. After the Berlin Wall came down, they were booked for a tour of the Czech Republic. It was six days of no sleep, cheap Staropramen and Budvar, interested girls and angry anti-capitalist boys, military police escorts and backstage looting. They returned to play the Plaspop festival, in front of 25,000, alongside Oakland greats Tower of Power. They supported Dream Theater and opened at Paradiso in Amsterdam for a bizarre Australian Queen tribute act in the immediate aftermath of Freddie Mercury’s death . Queen fans traveled from far and wide to see – four showroom dummies. The ‘tribute’ was an art project, angrily received, and Topaz’s getaway was sweaty and swift. The band members were driven; they always gave their all. Topaz first appeared live on air, giving it the full live show package – on radio – half an hour after Vincent was in a car accident.

This is the part of the story, most stories, where progress stalls. Pretty much every nineties rock or blues musician’s story has the chapter on falling out of favor as grunge sweeps up a generation, but this isn’t that story. In this story, the Dutch live music scene was changing, and the rug was about to be pulled out from under Topaz.

Vincent’s band was top notch. The band that musicians came to watch. Mojo Concerts was fast becoming the gatekeeper to music venues across the Netherlands and would soon be the only game in town. They wanted Topaz on their roster. Mojo would book and promote their shows, but Winston wasn’t part of the deal. They gave Vincent the hard sell. Come and meet Van Halen backstage, see your future.

No Winston, no deal. Vincent turned Mojo down. Almost overnight, big festivals and local venues were closed off. The final nail was an end to government subsidies for live music venues. Concert venues paid well until suddenly they couldn’t. House music was taking hold and club crowds could take up the slack. Topaz would finish their set in front of fifty just as the club DJ took up his position and a thousand clubbers swarmed in.

Players gotta play. Vincent was just as at home in the studio as on stage, but his band needed the red meat of gigs to keep going. The band disbanded.

For a while, Vincent owned a live music club which allowed him to keep playing but, as ever, life takes over. Having left the Gymnasium (high school) at seventeen, he started taking some computer science classes. He made the move to Ireland, worked his way up in Microsoft, and relocated to Seattle with actor/Microsoft wife Catherine.

Vincent’s home studio overlooks a backyard that stretches into woods, a red swing the marker of a young family. Lined up below the waist-level window sill is the guitar collection that the six-year-old, Kiss-obsessed Vincent would hope his forty-something version would have. One signed by Steve Morse of Deep Purple and Dixie Dregs, one from the short-lived Valley Arts Guitars, and guitars from John McGuire whose store went down when someone torched the Tier 1 Imports next door. His guitars were worked on by Mike Lull who Vincent would invent reasons to visit until his recent passing, just to hear stories from forty-odd years making guitars for Cheap Trick, Pearl Jam, Heart and more.

Vincent’s story is peppered with characters – musicians and managers, industry figures and friends – all now spread across three continents. He tinkers in his home studio, his army of guitars huddled around, on the march to playing live again. Because, like every passion that the pantomime of rock and roll TV sparked, there is a fire that will never go out.